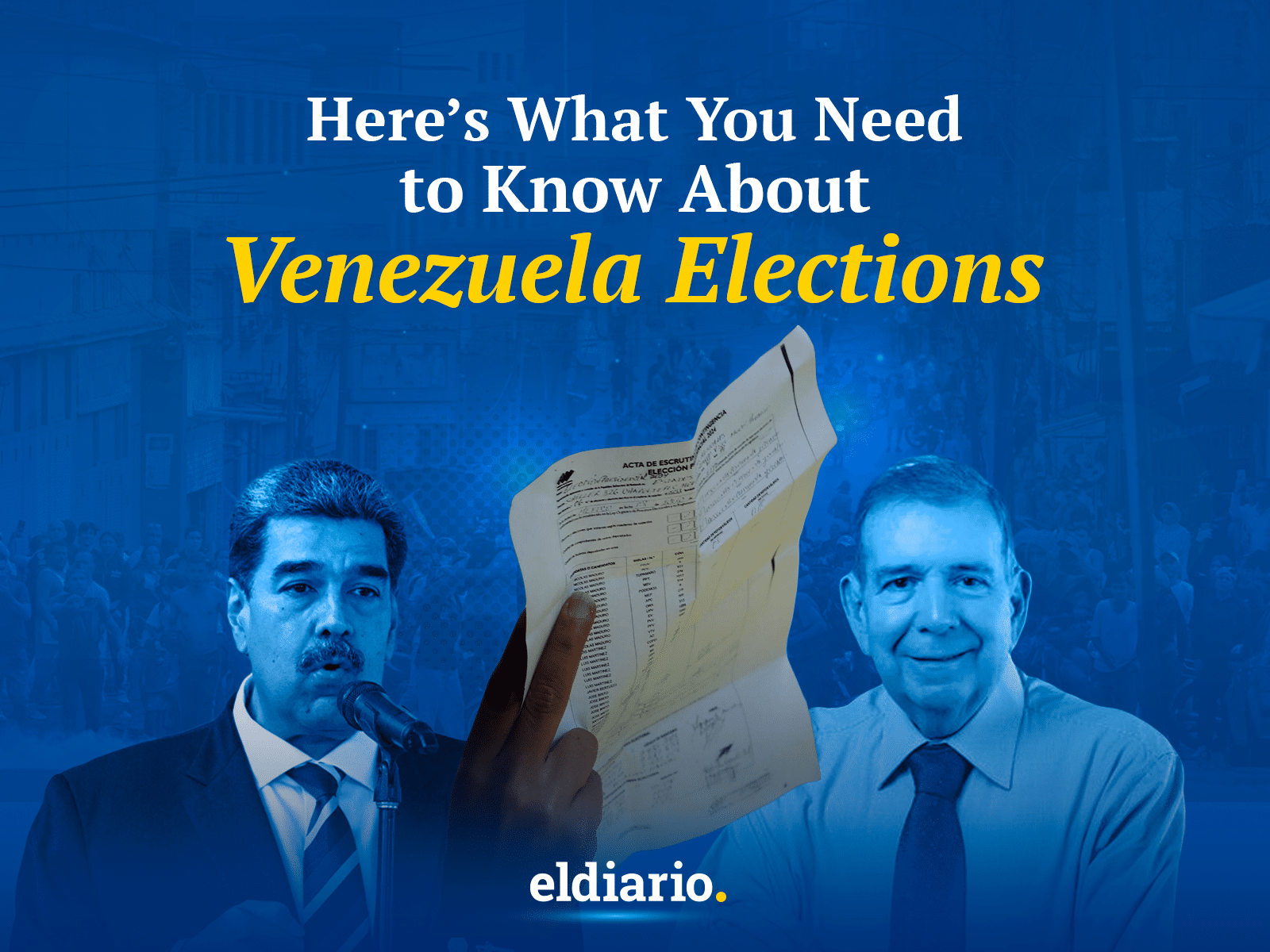

- The country is facing a political crisis after the National Electoral Council proclaimed Nicolás Maduro as the winner of the presidential elections without publishing the tally sheets, known as ‘actas’, which —according to the opposition’s published voting results— favor Edmundo González. This situation has unleashed a wave of protests and repression, keeping the international community on high alert

Venezuela stands at a turning point in its recent history. The presidential elections held on July 28 have raised doubts about the data from the National Electoral Council (CNE), which announced results declaring Nicolás Maduro the winner amid a process that has been questioned by both the opposition and the international community.

The campaign led by María Corina Machado asserts that the opposition candidate, Mr. Edmundo González, from the Democratic Unitary Platform (PUD), was the true winner of the elections, claiming over 67 % of the votes. This assertion is based on copies of the electoral tally sheets collected by ‘testigos electorales’ —poll watchers— from the opposition at each polling station, while the CNE has so far avoided making this information public, citing an alleged cyberattack.

The international community has been closely monitoring the situation, with countries like the United States, Colombia, and Brazil calling for the release of the tally sheets to determine the true winner of the elections. In the meantime, citizens in various parts of Venezuela have taken to the streets to protest the results. Security forces have suppressed these demonstrations, resulting in at least 11 deaths and thounsand of arrests.

In light of the complexity and uncertainty surrounding the Venezuelan political landscape, El Diario provides an overview of the context behind the voting process:

Election Announcement

On March 5, 2024, marking the 11th anniversary of Hugo Chávez’s death, CNE broke weeks of silence to announce its electoral schedule. July 28 was selected as the election date, coinciding with the birthday of the former president and proposed by the Patriotic Pole (GPP) —a coalition of ruling parties that backs Maduro and the so-called Bolivarian Revolution— and its allies.

Other reports denounced the presence of ‘consejos comunales’ (community councils) —which are citizen organizations subordinate to the government— performing CNE tasks at registration points or maintaining parallel voter lists. Additionally, numerous incidents were reported, including electrical outages and internet failures that hindered the process, as well as slow response times from officials.

Finally, on April 17, the chief rector of the National Electoral Council, Elvis Amoroso, announced that 604,964 new voters had registered in the voter registry, and 847,999 had changed their voting centers. This was despite independet organizations like Voto Joven estimating that over 3.5 million Venezuelans were not registered in the voter registry.

Voters Abroad

During this special registration period, Venezuelans living abroad were also able to register or update their information in the voter registry. According to Súmate —a Venezuelan civil association that facilitates citizen participation processes— of the nearly 8 million Venezuelans in the diaspora, around 4.5 million were eligible to vote, having registered in their home country.

However, the registration process abroad was marred by multiple irregularities. Several consulates, including those in Argentina and Spain, opened days late and limited their hours of operation, as well as the number of people allowed to register each day. In other cases, residency documents that did not reflect the reality of migrants were required, such as in Colombia, where the temporary protection permit (PPT) was not recognized as valid.

Ultimately, according to the CNE, 508 new voters were able to register abroad, and 6,020 updated their residency information. By the final Electoral Register cutoff in April 2024, only 69,211 eligible voters were registered abroad, representing approximately 1.54% of Venezuelan citizens living overseas who had the right to vote. Nevertheless, many Venezuelans returned to their country in the days leading up to July 28 with the intention of casting their votes.

Disqualifications and Restrictions

While campaigning in the opposition’s primary elections, María Corina Machado was politically disqualified on June 30, 2023, by the General Comptroller’s Office, then led by Elvis Amoroso, the current president of the CNE. As a result of the Barbados Agreement —a pact between the government and the opposition to primarily guarantee free and fair elections—, the opposition leader attempted to appeal the decision in the supreme court (TSJ) in December, but her request was denied. This created a dilemma regarding the opposition’s candidate for the elections.

On March 21, the registration process for candidates began, but Machado was unable to participate in the elections. It was then unanimously agreed by the PUD and Vente Venezuela —the political party of Ms. Machado— to nominate academic Corina Yoris, who had no disqualifications or previous government involvement. Nevertheless, the Democratic Unitary Platform reported on March 23 that the CNE’s system continued to block her registration without any apparent justification.

The Democratic Unitary Platform sent several communications to the CNE, including a request for an extension, but received no response. The registration process closed on March 25 without Yoris or any other alternative candidates being able to register, as the system remained blocked. This prompted the opposition parties to nominate candidates independently, with Un Nuevo Tiempo (UNT), Movimiento por Venezuela (MPV), and Fuerza Vecinal registering Zulia Governor Manuel Rosales, while the Centrados party was authorized to nominate Enrique Márquez.

The deadline passed without the Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (MUD), the main opposition coalition that includes the UNT and MPV parties, being able to register a candidate from the PUD. However, on March 26, Edmundo González was administratively registered as a ‘placeholder candidate’ while the blockage on primary opposition options was being resolved, which they claimed was directly ordered by the government to the CNE.

Unitary Platform and the Obstacles

After several meetings and internal negotiations, the Democratic Unitary Platform unanimously agreed on April 19 that Edmundo González would remain the main opposition candidate. This decision was made in light of the risk of disqualification or obstruction if they attempted to replace him with another candidate.

The process for substituting candidates that would appear on the ballot was set to close on April 20. At that time, the UNT and MPV parties reported a new blockage on the CNE’s website that prevented them from formalizing the change. They were also denied entry at the agency’s headquarters, even though other candidates were allowed to complete the same process while opposition representatives waited at the door.

Once the deadline passed, the CNE granted a three-day extension, during which, just hours before the closure on April 23, UNT and MPV were able to align themselves with González’s candidacy. Meanwhile, Fuerza Vecinal decided to support Antonio Ecarri, while Centrados maintained Márquez’s candidacy, albeit with close discussions with the Democratic Unitary Platform.

Judicially Intervened Political Parties

Several opposition parties, as well as critical pro-government parties, have been judicially intervened through rulings by the Supreme Tribunal of Justice. Among the first cases, from 2011 to 2012, were Copei, Bandera Roja, Patria para Todos (PPT), and Podemos, as well as MIN-Unidad, Movimiento Electoral del Pueblo (MEP), and Movimiento Ecológico, between 2013 and 2018.

The aim of these interventions was, in the case of dissenting pro-government parties, to forcibly keep them within the Gran Polo Patriótico, controlled by the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). For opposition parties, their names and symbols were handed over to leaders aligned with the government. As a result, in the presidential elections, of the 37 parties listed on the ballot, 13 were judicially intervened and supported candidates not recognized by their legitimate authorities.

International Observation

Another factor that generated concern during the elections was the absence of independent international observers. On May 28, the CNE revoked the invitation to the European Union’s mission after the EU ratified a package of economic sanctions against high-ranking officials of the Chavismo, curiously exonerating Elvis Amoroso himself.

In the days leading up to the elections, rising tensions and a lack of guarantees led the governments of Colombia and Brazil to withdraw their respective delegations, although Brazil eventually sent electoral expert Celso Amorim, a special advisor to President Lula da Silva on foreign policy. Other invited observers, such as former Argentine President Alberto Fernández, also had their invitations revoked for publicly expressing concern about the country’s situation.

Several international political figures attempted to enter Venezuela on July 26 to act as international observers but were rejected by the government. Among them were a delegation from Chile led by Senator Felipe Kast, another from Spain composed of members of the Popular Party (PP), and Colombian parliamentarians who were deported upon arrival at the airport.

Political Campaign and Persecution

From the very day the elections were called on March 5, 2024, both the government and the opposition began campaigning across the country. Despite being disqualified, Machado assumed the role of opposition leader with a car tour through various states. In many cases, she was followed by Chavista leaders such as Diosdado Cabello and Jorge Rodríguez, who held rallies in the same locations.

During this period, there was a notable increase in repression and persecution against citizens who assisted Mrs. Machado in her tours or provided services to her campaign. Examples include hotels closed by the Seniat —Venezuelan Tax and Customs Authority— and local businesses like a snack stand in Corozopando, a small town located in Guárico state, which gained international media attention. There were also arrests of activists, drivers, and sound equipment contractors, as well as individuals who spoke at Machado’s events.

***

On July 4, the campaign officially began with a couple of marches in Caracas organized by both the government and the opposition, which, despite being at some points in the city, concluded without incidents. However, political persecution intensified in the following days, resulting in over 90 detentions, primarily of local campaign leaders and businessmen like Ricardo Albacete, who was arrested for providing accommodation to Machado in Táchira, and whose warehouse was raided in an attempt to link him to alleged electrical sabotage.

In the final days of the campaign, two incidents also jeopardized the safety of Machado and Edmundo González. The first occurred at a restaurant in Aragua state on July 13, where a group of pro-government officials attacked them while they were having lunch. On July 18, in Lara state, unidentified individuals vandalized Machado’s vehicle, covering her windshield with paint and cutting the brakes.

Election Day

Throughout the campaign, Machado based her strategy for defending the vote on the Red 600 K (600K Network), a platform that trained over 90,000 poll watchers, as well as ‘comanditos’—small teams formed through citizen participation to assist with logistical tasks. Both structures proved crucial on July 28, the day of the election.

Earlier, Machado had urged citizens to participate in the citizen audit of the counting process, which helped pressure authorities to release the records. However, there were still reports of opposition observers being beaten and kidnapped by officials and ‘colectivos’, paramilitary groups aligned with the government. In the evening, armed collectives attacked the center located at John F. Kennedy School in the Guasimos municipality of Táchira state. Julio Valerio García, 40, was killed by a mortar blast to the face, and another individual was injured by gunfire.

Meanwhile, at the Comando con Venezuela —the opposition campaign headquarters— the main election observer for the Democratic Unitary Platform, Delsa Solórzano, reported being denied entry to the CNE to file reports of irregularities or to supervise the totalization of votes. Hours later, she warned that the electoral agency had halted the transmission of the records after only 30% of the votes had been counted.

Controversial Election Results

Despite the complaints made by Solórzano and other command spokespeople, such as Perkins Rocha, the CNE did not respond to any of their communications. At midnight, Amoroso appeared on camera to deliver the first bulletin with results, claiming that 80 % of the ballots had been counted. He announced that with a voter turnout of 59 %, Nicolás Maduro had won with 51.2 % (5.1 million votes), while González had reportedly obtained 44.2 % (4.4 million). There were no significant details regarding the other candidates, who collectively received just 4.6 % (462,000 votes).

Amoroso attributed the interruption of the transmission to a supposed cyberattack that delayed the counting process. Later, Attorney General Tarek William Saab, who is also aligned with the government, claimed that the attack originated in North Macedonia, although the government of that country denied it, prompting a shift in narrative to blame tech mogul Elon Musk instead.

Even though the official margin in these numbers was 700,000 votes, and the missing 20% of ballots represented approximately 2.5 million votes, Amoroso declared the results “irreversible” and hurried to proclaim Maduro on July 30. Five days later, without yet publishing the results from each polling station and with the CNE’s website down, he released a second bulletin confirming the incumbent’s victory with 96.87% of the ballots counted, widening his lead to 51.9% (6.4 million votes) against González’s 43.1% (5.3 million).

‘Actas’ in hand

In the early hours of July 29, María Corina Machado and Edmundo González addressed the nation, rejecting the results of the first bulletin from the National Electoral Council (CNE). They based their claims on exit polls and independent counts conducted during the scrutiny, which indicated a victory for the opposition candidate with nearly 70% of the votes. They planned to substantiate their claims with the tally sheets collected by their poll watcher members.

According to the portal Resultados con Venezuela, by August 2, the opposition had managed to recover 81.7% of the tally sheets. This allows them to present a seemingly irreversible result, with Edmundo González winning 67% of the votes (7.2 million), while Maduro garnered 30% (3.2 million). Currently, the portal and its backup pages are blocked by Venezuelan internet service providers at the order of the National Telecommunications Commission (Conatel).

Social Outburst

On July 29, the country woke up to the sound of cacerolazos (pot banging protests). In Caracas and several cities across the nation, spontaneous protests erupted as people rejected the CNE’s results favoring Maduro. These demonstrations were particularly intense in low-income neighborhoods, with disturbances reaching the heart of the capital, just a few blocks from Miraflores, the presidential palace.

All these protests were met with heavy repression by security forces, particularly the Bolivarian National Police (PNB). There were also reports of attacks by armed groups, allegedly ‘colectivos,’ who opened fire on the demonstrations. The Monitor de Víctimas —a victims’ monitoring NGO— estimates that out of 19 reported deaths during the post-election protests, six were caused by armed groups, three by the Bolivarian National Guard (GNB), one by the police, and several cases remain unresolved.

Almost all the deaths, as well as the reports of injuries, involved gunshot wounds. According to an independent survey by the organization Médicos por la Salud (doctors for health), other injuries among the wounded —including three minors— were caused by riot control measures such as rubber bullets and tear gas, as well as trauma to the chest, neck, and limbs.

Additionally, Attorney General Saab reported the death of a GNB sergeant in Aragua state and 48 injured officials. So far, Saab has denied the death of any protesters during the demonstrations, claiming they were “staged” with ketchup.

Doubts Surround the Process

The controversy over the election results has raised questions about the credibility of the Electoral Power in Venezuela. Various organizations and institutions have called on the Venezuelan government to allow the publication of the tally sheets to verify who the true winner of the elections is. This sentiment has also been echoed by international observers, including former presidents Ernesto Samper (Colombia) and Leonel Fernández (Dominican Republic).

After withdrawing its team from the country, the Carter Center —an organization recognized for its integrity by Venezuelan Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino López— released a statement declaring that the presidential election in Venezuela “did not meet international standards for electoral integrity and cannot be considered democratic.” The statement also dismissed the government’s claims of electoral hacking.

Former candidate Enrique Márquez spoke out, alleging that, according to his election observer present at the National Electoral Council on election day, the first bulletin read by Amoroso was not printed in the vote counting room as required by protocol, and he confirmed that his records do not match the official results. “I don’t know where that paper came from,” he stated. Even other pro-system opposition candidates, such as Antonio Ecarri, Claudio Fermín, and Javier Bertucci, have urged the CNE to publish the records.

International Position

The Venezuelan electoral crisis has had regional repercussions. While some countries like Bolivia, Honduras, and Nicaragua recognized Maduro’s victory, most expressed concern over the opacity of the results and joined the call for an audit to validate the transparency of the process. This includes the United States and the European Union.

Not all responses were well received. The Maduro government severed diplomatic relations with Peru, the first country to label the events as electoral fraud and recognize Edmundo González’s victory. It also expelled diplomatic representatives from Argentina, Costa Rica, Chile, the Dominican Republic, Uruguay, and Panama for questioning the CNE’s results.

This situation prompted an emergency meeting at the Organization of American States (OAS), where an agreement was proposed to demand that Venezuela publish the electoral records and respect the human rights of protesters. However, the motion did not receive the 18 votes needed for approval, garnering only 17 in favor, with 11 abstentions and 5 absences. No votes were cast against it.

On August 1, the United States became the second country to recognize González as the true winner of the elections. Shortly thereafter, the governments of Argentina, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Panama joined in this recognition. Meanwhile, the presidents of Colombia and Brazil, Gustavo Petro and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, are acting as mediators in alleged negotiations between Washington and Caracas to seek a peaceful resolution to the conflict.

Judicial Route

On July 31, Nicolás Maduro met with the judges of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice to file an electoral dispute concerning the election results. “I come before the highest court to request that it convene and summon, as is within its authority, all institutions and the 38 parties, and thoroughly examine what has transpired regarding this attack on polling centers and all the evidence”, he stated.

Next day, the Electoral Chamber of the Supreme Court granted the request and summoned the ten candidates to appear before the court. The tribunal also ordered them to submit their copies of the electoral records for investigation and verification.

The Democratic Unitary Platform dismissed participation in the session. Lawyers such as Perkins Rocha and Delsa Solórzano explained that the motion filed by Maduro before the TSJ has no basis in Venezuelan law. They stated that it is the CNE and the candidates who should be held accountable for the irregularities in the process, and that the Electoral Chamber lacks the authority to handle the totalization of results and declaration of a winner. They also noted the TSJ’s lack of credibility, evidenced by the arbitrary nature of its rulings, which are biased in favor of the government.

On August 2, a hearing took place at the TSJ with Maduro and all candidates, except for González Urrutia. Indeed, without conducting any investigation yet, the court president, Caryslia Rodríguez, certified the results as “irreversible” and called on those present to sign a notification document committing to recognizing the results. The only candidate who refused to sign was Enrique Márquez, who reiterated his demand for an independent audit of the voting records.

Repression

As uncertainty looms over the election results, Venezuela is descending into a spiral of repression and political persecution that has raised alarms in the international community. Attorney General Saab has reported that there are currently over a thousand people detained for post-election protests, with charges including terrorism and incitement to hatred expected to be filed against them.

Maduro himself stated on August 1 that he would adapt the Tocorón and Tocuyito prisons to accommodate the ‘guarimberos,’ as he refers to the protesters, declaring they would serve as “re-education centers.” He also urged his supporters to inform on opposition leaders or local demonstrators through apps like Ven App or messaging groups, which would be forwarded directly to intelligence agencies.

Meanwhile, the opposition has denounced a resurgence in the persecution of opposition observers and polling station members who participated in the primaries. Additionally, on August 2, the Vente Venezuela headquarters in Caracas was vandalized in an apparent attempt to steal the electoral records in their possession.

Nevertheless, despite having to take precautions for their safety, María Corina Machado and Edmundo González continue their grassroots activities to demand verification of the CNE records and prove the opposition’s victory in the elections. They have reiterated the peaceful, even familial nature of these demonstrations, despite the ruling powers’ refusal to facilitate a peaceful and democratic transition, which is dragging the country toward a new political crisis.

Traducción de José Gregorio Silva.